by Jennifer Lahl, CBC President

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: it almost always starts with an emotional story.

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: it almost always starts with an emotional story.

The

latest situation is an embryo custody battle in Arizona. It highlights

the depth of real human emotions connected to having children and

building a family, and the ways in which human lives are affected by a

justice system that seeks to do what is right in the midst of a true

ethical mess. As with all embryo custody battles, there are never any

winners. There are plenty of losers, though, and the embryos have the

most to lose by far.

This case, of course, tugs at our heartstrings. In 2014, at the age of thirty-three, Ruby Torres was diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer—a very aggressive breast cancer that has the lowest five-year survival rate

of all breast cancers. Torres was engaged at the time of her diagnosis.

Because her cancer treatments might leave her infertile, she and her

then-fiancé, Joseph Terrell, made the decision to undergo IVF to create

embryos and freeze them for later use. A contract was signed stipulating

that neither Torres nor Terrell “could use the embryos without the

written permission of the other person.” Soon after, they were married.

In

August 2016, Terrell filed for divorce and told the court that he did

not want to have children with Torres. The case is now in the courts of

Arizona, where there is no case law on the disposition of surplus

embryos once they have been created. On one side, Torres, who is now

infertile, is fighting for her “right to have her own biological

children.” Terrell, on the other side, is fighting for his “right not to

parent.”

A

Maricopa County Family Court judge recently ruled that the embryos must

be donated to a couple seeking embryo adoption or to a fertility clinic

since Torres and Terrell are not in agreement. Torres has filed a

notice of intent to appeal the ruling to the Arizona Court of Appeals.

There Ought to Be a Law

How

can we keep cases like this from happening in the future? Perhaps the

simplest way would be for the United States to adopt a policy similar to

Germany’s. The law there prohibits the creation of so-called surplus

human embryos. In Germany, only three embryos can be created in one IVF

cycle, and they must all be transferred into the mother’s womb.

But

embryo donation and adoption is big business in the United States.

Current estimates are that there are nearly three-quarters of a million

frozen embryos here. In addition, approximately 28 million federal dollars

are funding embryo donation programs, thus creating a whole new

industry, which shows no signs of being interested in putting itself out

of business.

Our

country is a long way from passing a law like Germany’s, in part

because we are so far down the path of embracing embryo adoption. We are

gripped by the emotional stories of “snowflake” children. Recall the

George W. Bush-era embryo battles over surplus human embryos being

either destroyed for cures or adopted into loving homes. Almost no one

pushed for a law banning the creation and freezing of human embryos

then—and almost no one is pushing for it now—which is one of the reasons

why this case in Arizona is so troublesome for the courts.

Souls on Ice

At the height of those embryo battles, Liza Mundy wrote in Mother Jones

about “Souls on Ice.” That was 2006, when the count of frozen embryos

was “only” about half a million. Mundy raised the question of embryo

disposition after speaking with a California couple who had fourteen

surplus frozen embryos. What should they do with them? Should they “Give

them away to another couple, to gestate and bear? Her own children’s

full biological siblings—raised in a different family? Donate them to

scientific research? Let them . . . finally . . . lapse?”

At the height of those embryo battles, Liza Mundy wrote in Mother Jones

about “Souls on Ice.” That was 2006, when the count of frozen embryos

was “only” about half a million. Mundy raised the question of embryo

disposition after speaking with a California couple who had fourteen

surplus frozen embryos. What should they do with them? Should they “Give

them away to another couple, to gestate and bear? Her own children’s

full biological siblings—raised in a different family? Donate them to

scientific research? Let them . . . finally . . . lapse?”

That was eleven years ago. Now the number of souls on ice is rapidly approaching three-quarters of a million.

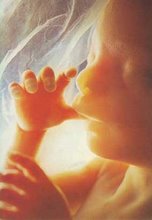

Human

life was not meant to be created in the lab, put on ice, and left for

years and years. Many frozen embryos do not survive the thawing process.

As Paul Ramsey

explained back in 1972, freezing human embryos would “constitute

unethical medical experimentation on possible future human beings, and

therefore it is subject to absolute moral prohibition.” Though the

medical community failed to heed his warning, Ramsey’s words are still

true:

My only point as an ethicist is that none of these researchers can exclude the possibility that they will do irreparable damage to the child-to-be. And my conclusion is that they cannot morally proceed to their first ostensibly successful achievement of the results they seek, since they cannot assuredly preclude all damage.

In

other words, it is thought to be safe to freeze, thaw, and transfer

human embryos into wombs, but the truth is that we are performing a

highly experimental procedure on human beings who cannot in any way

consent to the procedure they are undergoing. In fact, research is being

done on these children, following them over the course of their lives

to see how they fare. In what other circumstance would such treatment

not be considered horrific?

How can we clean up this mess?

Parents, Come Get Your Children!

As

I mentioned above, a good place to start is by legally limiting the

number of embryos that can be created and prohibiting the freezing of

embryos, as Germany does. But what about the embryos currently in

cryopreservation storage? We need a policy that would require the people

who created the embryos to make a decision. They can choose to transfer

the embryos into their mother’s body, donate them to an embryo adoption

agency, or allow them to thaw and die. I am open to discussions of ways

to incentivize transferring the embryos into the mother—this, in my

view, is what should happen, or being donated for embryo

adoption—but I am not open to having the embryos donated to scientific

research where they will be destroyed, killed.

The

human embryos who are currently abandoned in freezers were created for

the purpose of building families. The simple answer is for parents to

come and get their children. If you choose to abandon your embryos—that

is, your children—you can opt to “donate” them to someone who is willing

to bear and raise your child.

Embryo

adoption, though, is fraught with its own set of ethical issues. Anyone

choosing to donate their unwanted embryos or to adopt such embryos must

enter into such a decision with a clear mind about the problems that

are likely to arise.

Children

created in this way will face many difficult and troubling realities as

they come to know and understand their conception stories. They must

come to terms with the fact that they were created, abandoned, seen as

surplus and unwanted, and ultimately given away by their biological

parents. This can be an enormous burden for a child to carry. Given my

extensive work on issues around third-party conception—egg donation, sperm donation, and surrogacy—I

know all too well how likely it is that these children will grow up

longing to know their biological parents, siblings, and larger family

while at the same time feeling abandoned and perhaps even unloved.

Who Has Moral Obligations to Frozen Embryos?

Finally,

I hold that we, the general public, have no moral obligation to rescue

abandoned frozen embryos, just as we have no obligation to donate a

kidney. Such acts—supererogatory acts—are those that are good but not

morally required. I do believe, as I mentioned above, that the parents

who created the embryos have a moral obligation to reclaim their embryos

and have them transferred into the mother’s uterus. But that obligation

does not extend beyond the parents who brought them into being.

Physicians who assisted in creating and freezing embryos have broken

with the Hippocratic roots of medicine, inevitably harming some

embryos—that is, the ones that do not survive the freezing and thawing

process.

Depending

on where you are on the religious spectrum, you will find variations on

the exact nature of our moral duty to abandoned embryos and their right

to life. My own recommendation is to follow a pattern that Lutheran

theologian Gilbert Meilaender, Senior Research Professor at Valparaiso

University and Scholar at The Paul Ramsey Institute, recommends in his most recent book, Not by Nature but by Grace. He writes,

What Christians, at least, should want [with respect to abandoned embryos] is a brief religious ritual to accompany their dying, a liturgy in which we commend these weakest of human beings to God, though perhaps also a liturgy in which with the psalmists we ask God how long his providence will permit this to continue. . . . We demonstrate our humanity by accompanying frozen embryos to their death and committing them liturgically to God’s care.

But we must recognize, as the Catholic encyclical Donum vitae states,

In consequence of the fact that they have been produced in vitro, those embryos which are not transferred into the body of the mother and are called “spare” are exposed to an absurd fate, with no possibility of their being offered safe means of survival which can be licitly pursued.

Never

to know the nurturing environment of their mothers’ wombs and never to

be lovingly raised by their mothers and fathers, such embryos suffer an

absurd—and tragic—fate indeed.

This article originally appeared on The Public Discourse.