Wesley J. Smith, J.D., Special Consultant to the CBC

Nearly two decades have passed since the

birth of Dolly the sheep, a clone manufactured through a process known

as somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). Since that time, the prospect

of human cloning has been eagerly—or fearfully anticipated—throughout

the world. Indeed, in 2004, Korean scientist Huang wu-Suk became

generated world headlines when he claimed to have created the first

human cloned embryos and derived embryonic stem cells from them.

It later turned out that he had done no

such thing. Huang was a charlatan. But now, the very deed that briefly

made him the world’s most famous scientist has actually been

accomplished, and you can hear the crickets chirping.

Why the striking difference in attention paid to an epochal story?

When

Huang claimed to have successfully cloned human beings, it set off a

political firestorm, with human cloning proponents and opponents

debating hotly over how and whether to regulate human cloning, or

even—as I advocate—to ban it altogether.

Wanting to prevent another public

brouhaha, the scientists who actually did do human cloning—and the

Science Establishment—generally avoided using the C-word in the popular

media—instead claiming merely that stem cells were obtained from

“unfertilized eggs.” Thus, the

Wall Street Journal reported:

Scientists have used cloning

technology to transform human skin cells into embryonic stem cells, an

experiment that may revive the controversy over human cloning. The

researchers stopped well short of creating a human clone. But they

showed, for the first time, that it is possible to create cloned

embryonic stem cells that are genetically identical to the person from

whom they are derived.

That description missed an essential—and morally crucial—element: SCNT does not create stem cells, it manufactures a human embryo via asexual reproduction, from which stem cells can be derived just as with a fertilized embryo.

To better understand what is going on, let’s take a brief look at how SCNT is accomplished:

- First, take a skin or other cell (Dolly came from a mammary gland

cell, hence her naming as something of a joke after Dolly Parton);

- Remove the cell’s nucleus;

- Next take an egg and remove its nucleus;

- Place the skin cell nucleus where the egg nucleus used to be;

- Stimulate with an electric current or other means;

- If the cloning works, the properties of the egg transform into a one-celled embryo just as occurs after fertilization.

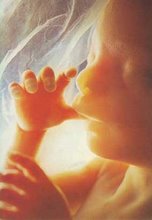

Once the embryo arises, the cloning is over. If all goes well, the embryo will develop like a natural embryo.

The next question involves what to do

with the living human life that was created. If the nascent human being

is to be destroyed for experimentation—as in this experiment—the process

is often called therapeutic cloning. If the intent is to implant in a

womb and bring a child to birth, it is often called “reproductive

cloning.” Either way, the actual cloning process is the same.

Indeed,

when the scientists talked to each other in the science journals, they

were far more candid about what had been done. Thus, in

the paper published in

Cell,

in which the scientists announced their cloning breakthrough, they

acknowledge to having created “SCNT embryos” From the study (my

emphasis):

Activation of embryonic genes and transcription from the transplanted somatic cell nucleus are required for development of SCNT embryos

beyond the eight-cell stage. Therefore, these results are consistent

with the premise that our modified SCNT protocol supports reprogramming

of human somatic cells to the embryonic state.

Why is this important morally? Scientists have manufactured human life.

In a sense, it is reproduction by replication—creating a new human

being designed to have a specific genetic makeup in the mirror image of

the person cloned. Even if the technique remains limited for use in

seeking biological knowledge and searching for potential medical

treatments, those beneficent ends will come at the very high ethical

price of manufacturing human life for the purpose of destroying and

harvesting it like a corn crop.

But it won’t end there. Human cloning is

the essential technology

to developing potential Brave New World technologies, such genetic

engineering, creating human/animal chimeras, gestating cloned fetuses in

artificial wombs as a means of obtaining patient-compatible organs, and

eventually, the birth of cloned babies. (We have already seen

advocacy for such fetal farming among a few bioethicists, and

experiments have already been conducted on late term aborted female fetuses to determine whether their ovaries can be harvested to obtain eggs for use in research.

Not only that, but human cloning heightens the risk that vulnerable women will be exploited for their eggs—the

essential ingredient

in SCNT—one egg per cloning attempt. Thus, it isn’t surprising that as

the rumors about successful human cloning were swirling through the

science community,

a bill was introduced

in the California Legislature—A.B. 926—that would permit universities

and their biotech partners to pay women for eggs to be used in

scientific research.

As the CBC documentary

Eggsploitation vividly demonstrates, supplying eggs can be dangerous to the woman’s health and fecundity.

This is the bottom line: Human cloning has been accomplished. We will either deal with it, or it will deal with us.

Wesley J. Smith is a special

consultant to the CBC. He is also a senior fellow at the Discovery

Institute’s Center on Human Exceptionalism.

When

Huang claimed to have successfully cloned human beings, it set off a

political firestorm, with human cloning proponents and opponents

debating hotly over how and whether to regulate human cloning, or

even—as I advocate—to ban it altogether.

When

Huang claimed to have successfully cloned human beings, it set off a

political firestorm, with human cloning proponents and opponents

debating hotly over how and whether to regulate human cloning, or

even—as I advocate—to ban it altogether.  Indeed,

when the scientists talked to each other in the science journals, they

were far more candid about what had been done. Thus, in

Indeed,

when the scientists talked to each other in the science journals, they

were far more candid about what had been done. Thus, in  But it won’t end there. Human cloning is the essential technology

to developing potential Brave New World technologies, such genetic

engineering, creating human/animal chimeras, gestating cloned fetuses in

artificial wombs as a means of obtaining patient-compatible organs, and

eventually, the birth of cloned babies. (We have already seen

But it won’t end there. Human cloning is the essential technology

to developing potential Brave New World technologies, such genetic

engineering, creating human/animal chimeras, gestating cloned fetuses in

artificial wombs as a means of obtaining patient-compatible organs, and

eventually, the birth of cloned babies. (We have already seen