On the first floor of the Dar al-Shifa hospital in Aleppo, a boom sounds as a rocket fired from a helicopter hits a nearby building, and the staff begin preparing for another influx of patients.

They barely flinch at the sound of the attack, which hits a fifth-floor apartment some 150 metres (yards) from the facility. The hospital itself has been shelled four times, forcing the evacuation of all but two of its floors.

"My God, it's like this every day," a nurse sighs as she rushes towards the hospital's front door to meet a car carrying wounded children, even as the helicopter continues to circle overhead, firing cannon rounds.

Two children are rushed in, a boy and a girl, blood streaming from their heads. Dust cakes their faces, arms and clothes.

Eight-year-old Mahmud struggles to get his words out as he sits on a stretcher, doctors rubbing iodine on his head as his chest heaves beneath his Barcelona football club shirt.

"We were sitting on the floor of the kitchen, me and my sister Sana, and a rocket came and hit the house. We didn't see the ceiling collapsing on top of us," he says.

"My mum and dad are still there," Sana cries next to him, her bare feet hanging over the edge of the bed, blood mixed with bits of concrete in her reddish hair.

"Where is my mum? Is she okay?" she weeps, as staff try to calm her down.

Both children have fairly minor injuries and are soon reunited with their parents. Their father rushes in first, followed by their grandfather, wild with panic, tears marking clean trails through the dust on his face.

Soon afterwards, their mother Fayha is pulled from the rubble and brought to the hospital. After the staff stitch up a wound to her head and wrap her in a blanket, she is brought for a family reunion.

In a small room nearby on the first floor, 25-year-old Mohammed, a general practitioner, is stitching up a wound on the arm of a fighter who was wounded by a grenade in the Saif al-Dawla neighbourhood, where fierce battles are raging between rebel forces and government troops.

"I've been here a month. I work four days at a time, full-time, treating everything that comes in," Mohammed says, asking an assistant to adjust a lamp so he can better see his stitching work.

"It's hard, of course, but I look at it as a duty, a humanitarian requirement."

The facility is barely a hospital now, able to handle only the simplest tasks -- stitches, blood transfusions, X-rays. The staff try to stabilise those in need of anything more so they can be transferred across the border to Turkey.

Most of the upper floors are unusable, with many rooms trashed by incoming shells, and the risk of repeated attack has prompted staff to confine their work to the two lowest floors and the basement.

On the first floor, a group of men run in carrying three children, two small boys and a tiny wide-eyed baby, his pale chest and downy hair covered in a film of white dust.

The fighter gets up from the bed he is on, dripping blood from his wounded arm on the floor, to make room for one of the children, four-year-old Mohammed.

The boy cries, gulping and sobbing, as nurses clean up the blood around his neck and shave away part of his hair to get at the wound he sustained when the same helicopter shot a rocket at his home, elsewhere in the neighbourhood.

"Be brave, you're a man, you mustn't cry," one of the fighters tells him gently, as strands of his shorn hair tumble onto his lap.

One bed over is 11-year-old Walid, who writhes as the hospital staff examine his wound. A shell exploded next to him as he was collecting rubbish, gouging out a deep wound around the bottom of his ribcage.

"I want water, I want water," he screams, as more than one of the men in the room turn away, trying to hide welling tears.

Abu Mohammed, the hospital pharmacist, maintains his cool. After a month working in the facility, he has learned to keep his emotions in check.

"Every day we are being shelled, and most of the people we see here are civilians, women and children. The sound of shelling, and the sound of screaming, have become something normal for us."

The 28-year-old started out working in a secret clinic in Anadan, a small town outside Aleppo, but moved into the city to work at the hospital when fighting between government troops and the rebel forces intensified.

"I look at it as my way of helping the revolution. I can't fight, but medicine is my skill and I can use it to help."

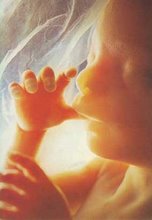

Were there to be no support in the whole history of ethical and moral thought, were there no acknowledged confirmation from medical science, were the history of legal opinion to the contrary, we would still have to conclude on the basis of God's Holy Word that the unborn child is a person in the sight of God. He is protected by the sanctity of life graciously given to each individual by the Creator, Who alone places His image upon man and grants them any right to life which they have.

Saturday, August 25, 2012

Hospital staff brave shells to treat wounded

via news.yahoo.com