| |||||

|

That is an outrageous allegation that is not only incorrect, but an insult to the sacrifices my parents made to provide a better life for their children. They claim I did this because "being connected to the post-revolution exile community gives a politician cachet that could never be achieved by someone identified with the pre-Castro exodus, a group sometimes viewed with suspicion."

If The Washington Post wants to criticize me for getting a few dates wrong, I accept that. But to call into question the central and defining event of my parents' young lives - the fact that a brutal communist dictator took control of their homeland and they were never able to return - is something I will not tolerate.

My understanding of my parents' journey has always been based on what they told me about events that took place more than 50 years ago - more than a decade before I was born. What they described was not a timeline, or specific dates.

They talked about their desire to find a better life, and the pain of being separated from the nation of their birth. What they described was the struggle they faced growing up, and their obsession with giving their children the chance to do the things they never could.

But the Post story misses the point completely. The real essence of my family's story is not about the date my parents first entered the United States. Or whether they travelled back and forth between the two nations. Or even the date they left Fidel Castro's Cuba forever and permanently settled here.

The essence of my family story is why they came to America in the first place; and why they had to stay.

I now know that they entered the U.S. legally on an immigration visa in May of 1956. Not, as some have said before, as part of some special privilege reserved only for Cubans. They came because they wanted to achieve things they could not achieve in their native land.

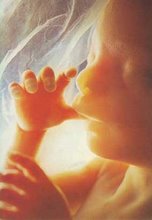

Image via Wikipedia

In February 1961, my mother took my older siblings to Cuba with the intention of moving back. My father was wrapping up family matters in Miami and was set to join them.

But after just a few weeks, it became clear that the change happening in Cuba was not for the better. It was communism. So in late March 1961, just weeks before the Bay of Pigs invasion, my mother and siblings left Cuba and my family settled permanently in the United States.

Soon after, Castro officially declared Cuba a Marxist state. My family has never been able to return.

I am the son of immigrants and exiles, raised by people who know all too we

Image via Wikipedia

My father spent the last 50 years of his life separated from the nation of his birth. Separated from his two brothers, who died in Cuba in the 1980s. Unable to show us where he played baseball as a boy. Where he met my mother. Unable to visit his parents' grave.

My mother has spent the last 50 years separated from her native land as well. Unable to take us to her family's farm, to her schools or to the notary office where she married my father.

A few years ago, using Google Earth, I attempted to take my parents back to Cuba. We found the rooftop of the house where my father was born. What I wouldn't give to visit these places where my story really began, before I was born.

One day, when Cuba is free, I will. But I wish I could have done it with my parents.

The Post story misses the entire point about my family and why their story is relevant. People didn't vote for me because they thought my parents came in 1961, or 1956, or any other year. Among others things, they voted for me because, as the son of immigrants, I know how special America really is. As the son of exiles, I know how much it hurts to lose your country.

Ultimately what The Post writes is not that important to me. I am the son of exiles. I inherited two generations of unfulfilled dreams. This is a story that needs no embellishing.Marco Rubio

Zemanta helped me add links & pictures to this email. It can do it for you too.