After 9 years of marriage, our little Thérèse Marie arrived on the feast-day of the Archangels in 2009. Great was our joy after all these years of waiting, longing, mourning, hoping and doubting that this would ever happen. We finally held our little daughter in our arms after 33 hours of labor ending in a C-section. I came to experience what so many mothers had told me about: the deep happiness of having a child, making you forget the pains of labor, and yearning to go through them all over again to have more children.

Our happiness seemed complete -- as much as it can be this side of the grave -- and the doctors gave us the hope that with the birth of one child, more children might be forthcoming. I felt the pangs of longing almost immediately, and each time I drove by the hospital, I hoped I might be returning there again soon for another delivery.

Women suffering from secondary infertility had told me about the pain which comes from having less children than one wants.[1] I even met one woman who was distraught since she had hoped for a ninth child which now, that she had had a hysterectomy in her mid-40s, would never be born. I tried to empathize; it seemed a real pain, but it didn't quite prepare me for what was to come.

Don't get me wrong. It makes a universe of difference to have one child rather than none. The joy of parenting is there, day after day, discovering the world anew through one's child's eyes, and feeling her love in so many ways. One's life has changed its focus and is centered on the growth and well-being of this little one.

But then the longing grows very strong again, one looks at one's medical options, wonders which therapies one should try this time and is sad at the thought that one's child might not have any siblings or less than one would want. I've written about the pain which comes from lack of empathy concerning infertility; it is just as real with secondary infertility.

Infertile couples tend to get less understanding, since people are under the impression that they are now "healed" and that they should be perfectly happy since they finally have a child. It can be unnerving to have witnessed the pain of infertility in a couple for many years, and now that they have a child and should be joyful (so one thinks), to see that they are still suffering; this seems to border on the ungrateful and indicate a negative outlook on life -- at least that's the feedback infertile couples can get.

But one can be very happy about having a child or children, and yet mourn deeply that one doesn't have more. Obviously the experience and cross is very different for the couple who is blessed with an abundant fertility; they too may be very glad about each one of their children, and yet feel crushed by fatigue and worries. In both cases joy and suffering can go hand-in-hand, and it takes Christian charity to empathize with each other -- the fertile and the infertile -- in situations which are polar opposites.

Making it difficult to bear the other's complaints -- and it is good to be aware of this -- can be one's own unacknowledged suffering; how can that other person be complaining about too many or too few children, when I am dead-tired because my children don't allow me to sleep or I am in deep pain since I haven't been given the gift of abundant fertility -- is something one may well ask oneself.

The problem lies not so much with the other person expressing her suffering, but with the fact that my pain hasn't been heard, that I've perhaps been stoic about it. It's a reminder that we often do not know each other's hidden crosses, and that we may well drive another nail in without knowing it.

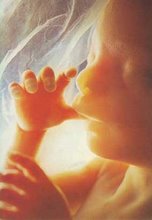

If one's history of infertility includes miscarriages, the pain is very intense. Most women suffer acutely from miscarriages, no matter what their story is. If they longed for children for an extended period, then a miscarriage breaks open the pain of their infertility in a new way. It feels like a nasty trick: they are given a child briefly, only to have it snatched away before they've even held her in their arms. It often takes much grieving under the Cross to be able to accept this loss and not blame God.

Even though it is a consolation to know we will meet our children in Heaven, this does not do away with the grief of missing this child here and now. This hope should not be used in an attempt to shorten the grieving-process either by oneself or by others.

Mother Teresa spoke of our "hidden Calcuttas." Each one has some deep pain, some existential wound which he tries to coat over, forget, and from which he wants to run away. If one tries to escape it, it has a way of catching up and hanging like a millstone around one's neck. There seems no adequate human answer for it, no real consolation.

The only person capable of responding fully to this seemingly infinite pain is Christ; He wants to be invited into the hidden Calcuttas of our grief and sin. He alone, being the Truth, can fully see and acknowledge our suffering and help us carry it instead of adding further pain through denial and lack of compassion. Only if carried with Him are we free to experience joy and fully empathize with another's pain without being distracted by our own. And only if we are transformed sufficiently by Him, are we able to stand with others under the Cross and be of true comfort.

[1] Secondary infertility is generally defined as not being able to conceive or carry a pregnancy to term within 12 months (if one is under 35) or within 6 months (if one is 35 or over) after one's cycle has started again.

This article was originally printed on Human Life International's Truth and Charity Forum.