Health Care and The Common Good

From the homepage of the Denver archdiocese on August 26:  Last week a British Catholic journal, in an editorial titled "U.S. bishops must back Obama," claimed that America's bishops "have so far concentrated on a specifically Catholic issue - making sure state-funded health care does not include abortion - rather than the more general principle of the common good."

Last week a British Catholic journal, in an editorial titled "U.S. bishops must back Obama," claimed that America's bishops "have so far concentrated on a specifically Catholic issue - making sure state-funded health care does not include abortion - rather than the more general principle of the common good."

It went on to say that if U.S. Catholic leaders would get over their parochial preoccupations, "they could play a central role in salvaging Mr. Obama's health-care programme."

The editorial has value for several reasons. First, it proves once again that people don't need to actually live in the United States to have unhelpful and badly informed opinions about our domestic issues. Second, some of the same pious voices that once criticized U.S. Catholics for supporting a previous president now sound very much like acolytes of a new president. Third, abortion is not, and has never been, a "specifically Catholic issue," and the editors know it. And fourth, the growing misuse of Catholic "common ground" and "common good" language in the current health-care debate can only stem from one of two sources: ignorance or cynicism.

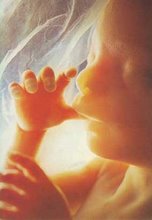

No system that allows or helps fund - no matter how subtly or indirectly -- the killing of unborn children, or discrimination against the elderly and persons with special needs, can bill itself as "common ground." Doing so is a lie.

On the same day the British journal released its editorial, I got an email from a young couple on the east coast whose second child was born with Down syndrome. The mother's words deserve a wider audience:

Magdalena "consumes" a lot of health care. Every six months or so she's tested for thyroid disease, celiac disease, anemia, etc. In addition, she's been hospitalized a few times for smallish but surely expensive things like a clogged tear duct, feeding studies and pneumonia (twice). She sees an ENT regularly for congestion, she requires a doctor's prescription for numerous services - occupational therapy, physical therapy, feeding, speech, etc. -- and she needs more frequent ear and eye exams.

I could go on. Often, she has some mysterious symptoms that require several tests or doctor visits to narrow down the list of possible issues. On paper, maybe these procedures and visits seem excessive. She is, after all, only 3 years old. We worry that more bureaucrats in the decision chain will increase the likelihood that someone, somewhere, will say, "Is all of this really necessary? After all, what is the marginal benefit to society for treating this person?"

What do we think of the [Congressional and White House health-care] plans? A government option sounds dangerous to us. The worst-case scenario revolves around someone in Washington making decisions about Magdalena's health care; or, worse yet, a group of people -- perhaps made up of the same types of people who urged us to abort her in the first place. In general, we feel that policy decisions should be made as close as possible to the people who will be affected by them. We are not wealthy people, but our current set up suits us just fine. We trust our pediatrician, who knows us very well, who hears from us personally every few months, who knows Magdalena and clearly sees her value, to give us good advice and recommend services in the appropriate amounts.

We are unsure and uneasy about how this might change. We worry that we, and Magdalena's siblings, will somehow be cut out of the process down the line when her health issues are sure to pile up. I can't forget that this is the same president [Obama] who made a distasteful joke about the Special Olympics. He apologized through a spokesman . . . [but] I truly believe that the people around him don't know -- or don't care to know -- the value and blessedness of a child with special needs. And I don't trust them to mold policy that accounts for my daughter in all of her humanity or puts "value" on her life.

Of course, President Obama isn't the first leader to make clumsy gaffes. Anyone can make similar mistakes over the course of a career. And the special needs community is as divided about proposed health-care reforms as everyone else.

Some might claim that the young mother quoted here has misread the intent and content of Washington's plans. That can be argued. But what's most striking about the young mother's email -- and I believe warranted -- is the parental distrust behind her words. She's already well acquainted, from direct experience, with how hard it is to deal with government-related programs and to secure public resources and services for her child. In fact, I've heard from enough intelligent, worried parents of children with special needs here in Colorado to know that many feel the current health-care proposals pressed by Washington are troubling and untrustworthy.

Health-care reform is vital. That's why America's bishops have supported it so vigorously for decades. They still do. But fast-tracking a flawed, complex effort this fall, in the face of so many growing and serious concerns, is bad policy. It's not only imprudent; it's also dangerous. As Sioux City's Bishop R. Walker Nickless wrote last week, "no health-care reform is better than the wrong sort of health-care reform."

If Congress and the White House want to genuinely serve the health-care needs of the American public, they need to slow down, listen to people's concerns more honestly -- and learn what the "common good" really means.