From http://www.calcatholic.com/

Fathers for Good, an initiative for men by the Knights of Columbus, on July 29 interviewed Matt Lickona, of La Mesa CA for their website. Here is the interview:

Matthew Lickona, 36, is a young Catholic writer on the staff of the weekly San Diego Reader. He is author of the book Swimming With Scapulars(Loyola Press), a thoughtful collection of essays about being Catholic in today’s world. Lickona lives with his wife, Deirdre, and their six children in La Mesa, California, where Fathers for Good reached him by e-mail.

Matthew Lickona, 36, is a young Catholic writer on the staff of the weekly San Diego Reader. He is author of the book Swimming With Scapulars(Loyola Press), a thoughtful collection of essays about being Catholic in today’s world. Lickona lives with his wife, Deirdre, and their six children in La Mesa, California, where Fathers for Good reached him by e-mail.

Fathers for Good: Your book Swimming With Scapulars is a very readable memoir about growing up Catholic and the particular worldview that it can bring. What inspired you to write the book?

Lickona: Jim Holman, who owns the San Diego Reader, also edited a number of monthly Catholic newspapers, which have since been folded into the website California Catholic Daily. In late 1998, he asked me to begin writing a column for one of those papers, the San Diego News Notes, focusing on my spiritual life.

After five years or so, friends and family started encouraging me to write a book based on the columns. And as I looked them over, I began to think they might resonate with others who shared my sensibility, and my belief that orthodox Catholicism offered more than lockstep exterior unity. That it was, in fact, interested in preserving and promoting what was truly human, for the sake of leading humanity to ultimate unity with the divine.

In Scapulars, I tried hard to ground the life of faith in ordinary, everyday experience: going to school, falling in love, marrying, starting a family, attending Mass. I tried to keep the point of Christianity – God’s love redeeming sinful man – always in view, which meant an honest discussion of sin and its effects in my life. In short, I tried to make it a memoir, and not a spiritual treatise.

FFG: You had a solid Catholic upbringing. Did you ever rebel or fall away from the faith?

Lickona: My father, Thomas Lickona, is a psychologist and educator specializing in the moral development of children. My mother, Judith Lickona, mostly stayed home and ran the household. Both Mom and Dad have been Catholic all their lives, though both found themselves entering more deeply into the life of faith as I grew up. It was indeed a solidly Catholic upbringing – Sunday Mass, followed by discussion of Sunday Mass. Quick family rosaries on car trips. Family involvement in corporal works of mercy – fasting and sending money to the poor. Family involvement in the defense of the unborn – taking the bus to D.C. with Mom to attend the March for Life. And lots and lots of conversations about theology, Scripture, the life of the Church.

I never really rebelled, thanks in part to what I remember as a near constant stream of conversation growing up. We ate dinner together nearly every night, and there was almost always a topic that served to give structure to the talk. Because talk was a habit, my standard teenage withdrawal didn’t manage to isolate me from the rest of my family. (It helped that I held my brother Mark in high regard.) When I realized I wasn't sure if I believed in God any more, shortly before my Confirmation, I told my dad about it. He responded by watching and then discussing with me the video series Jesus Then and Now, which proved an enormous help. And as I went through high school, trying to take my faith seriously became its own sort of rebellion.

FFG: How are you raising your own kids in the faith? Are the challenges greater today?

Lickona: Well, I’d say that the first thing I’m doing is imitating my parents’ practice of conversation. I’m fortunate enough to work from home, and so I see a lot of my kids. I don’t sit down and give them religious lectures, but I’m around to answer questions, and to ask some of my own. I’ve been happy to find that sometimes, those conversations stick. The one time I make it formal is on Sunday, when we discuss what we remember from Mass and comment upon it.

The second – which I should do more of – is involving them in works of charity. My wife is better at this than I am. But last Advent, we did manage to make a bunch of lunches and then drive around downtown San Diego distributing them to the homeless. It was wonderful to watch my oldest son move from the fear of approaching a suffering stranger to a kind of delight in doing good, and a recognition of humanity in distress.

The third thing – which I should do a lot more of – is family prayer.

I don’t know if the challenges are greater today. I suppose in some way they are. But it seems to me that, even if they’re greater in degree, they’re the same in kind.

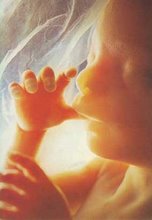

FFG: You’ve also worked on a comic book about abortion, called Alphonse. Are you trying to bring the pro-life issue to a popular medium?

Lickona: I am, indeed. Alphonse is a work of pop culture, just like the movie Juno, just like Ben Folds’ song "Brick." Stories shape the culture even more than law, I’d argue, and the culture seems to be opening up to stories that address this most radioactive of topics. I’ve tried to do it in a way that keeps everybody human – in a way that makes it a story and not a polemic.

FFG: What defines a Catholic writer?

Lickona: I’m going to stick with Catholic author Flannery O'Connor, who said that Catholic writing arises from a Catholic mind looking at anything. For someone with a Catholic understanding, creation has a certain shape and meaning, however fractured that shape or obscured that meaning, and that’s going to shine through in the writing.

To read this interview online, click here: click here.

Matthew Lickona, 36, is a young Catholic writer on the staff of the weekly San Diego Reader. He is author of the book Swimming With Scapulars(Loyola Press), a thoughtful collection of essays about being Catholic in today’s world. Lickona lives with his wife, Deirdre, and their six children in La Mesa, California, where Fathers for Good reached him by e-mail.

Matthew Lickona, 36, is a young Catholic writer on the staff of the weekly San Diego Reader. He is author of the book Swimming With Scapulars(Loyola Press), a thoughtful collection of essays about being Catholic in today’s world. Lickona lives with his wife, Deirdre, and their six children in La Mesa, California, where Fathers for Good reached him by e-mail.Fathers for Good: Your book Swimming With Scapulars is a very readable memoir about growing up Catholic and the particular worldview that it can bring. What inspired you to write the book?

Lickona: Jim Holman, who owns the San Diego Reader, also edited a number of monthly Catholic newspapers, which have since been folded into the website California Catholic Daily. In late 1998, he asked me to begin writing a column for one of those papers, the San Diego News Notes, focusing on my spiritual life.

After five years or so, friends and family started encouraging me to write a book based on the columns. And as I looked them over, I began to think they might resonate with others who shared my sensibility, and my belief that orthodox Catholicism offered more than lockstep exterior unity. That it was, in fact, interested in preserving and promoting what was truly human, for the sake of leading humanity to ultimate unity with the divine.

In Scapulars, I tried hard to ground the life of faith in ordinary, everyday experience: going to school, falling in love, marrying, starting a family, attending Mass. I tried to keep the point of Christianity – God’s love redeeming sinful man – always in view, which meant an honest discussion of sin and its effects in my life. In short, I tried to make it a memoir, and not a spiritual treatise.

FFG: You had a solid Catholic upbringing. Did you ever rebel or fall away from the faith?

Lickona: My father, Thomas Lickona, is a psychologist and educator specializing in the moral development of children. My mother, Judith Lickona, mostly stayed home and ran the household. Both Mom and Dad have been Catholic all their lives, though both found themselves entering more deeply into the life of faith as I grew up. It was indeed a solidly Catholic upbringing – Sunday Mass, followed by discussion of Sunday Mass. Quick family rosaries on car trips. Family involvement in corporal works of mercy – fasting and sending money to the poor. Family involvement in the defense of the unborn – taking the bus to D.C. with Mom to attend the March for Life. And lots and lots of conversations about theology, Scripture, the life of the Church.

I never really rebelled, thanks in part to what I remember as a near constant stream of conversation growing up. We ate dinner together nearly every night, and there was almost always a topic that served to give structure to the talk. Because talk was a habit, my standard teenage withdrawal didn’t manage to isolate me from the rest of my family. (It helped that I held my brother Mark in high regard.) When I realized I wasn't sure if I believed in God any more, shortly before my Confirmation, I told my dad about it. He responded by watching and then discussing with me the video series Jesus Then and Now, which proved an enormous help. And as I went through high school, trying to take my faith seriously became its own sort of rebellion.

FFG: How are you raising your own kids in the faith? Are the challenges greater today?

Lickona: Well, I’d say that the first thing I’m doing is imitating my parents’ practice of conversation. I’m fortunate enough to work from home, and so I see a lot of my kids. I don’t sit down and give them religious lectures, but I’m around to answer questions, and to ask some of my own. I’ve been happy to find that sometimes, those conversations stick. The one time I make it formal is on Sunday, when we discuss what we remember from Mass and comment upon it.

The second – which I should do more of – is involving them in works of charity. My wife is better at this than I am. But last Advent, we did manage to make a bunch of lunches and then drive around downtown San Diego distributing them to the homeless. It was wonderful to watch my oldest son move from the fear of approaching a suffering stranger to a kind of delight in doing good, and a recognition of humanity in distress.

The third thing – which I should do a lot more of – is family prayer.

I don’t know if the challenges are greater today. I suppose in some way they are. But it seems to me that, even if they’re greater in degree, they’re the same in kind.

FFG: You’ve also worked on a comic book about abortion, called Alphonse. Are you trying to bring the pro-life issue to a popular medium?

Lickona: I am, indeed. Alphonse is a work of pop culture, just like the movie Juno, just like Ben Folds’ song "Brick." Stories shape the culture even more than law, I’d argue, and the culture seems to be opening up to stories that address this most radioactive of topics. I’ve tried to do it in a way that keeps everybody human – in a way that makes it a story and not a polemic.

FFG: What defines a Catholic writer?

Lickona: I’m going to stick with Catholic author Flannery O'Connor, who said that Catholic writing arises from a Catholic mind looking at anything. For someone with a Catholic understanding, creation has a certain shape and meaning, however fractured that shape or obscured that meaning, and that’s going to shine through in the writing.

To read this interview online, click here: click here.