Assistive

reproductive technologies such as in vitro fertilization not only

involve serious medical risks, they also disrupt family life and

commodify human beings.

It almost always starts with an emotional

story: an infertile couple trying desperately to conceive; a woman

diagnosed with cancer, worried that she may lose her fertility when she

undergoes chemotherapy or radiation treatment; a couple with a dreaded

inheritable genetic disease that they do not want to pass on to their

children; a sick child in need of a transplant from a “savior sibling.”

And now added to the list is the same-sex couple or the single-by-choice

person who wants to conceive a biologically related child. Even

post-menopausal women can now—with the help of modern

technology—experience the joys of motherhood.

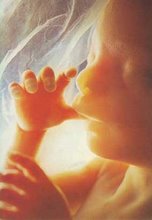

With the birth of Louise Brown

in 1978, the world’s first “test-tube baby,” the solution to

infertility was seemingly found in reproductive technologies. The

beginnings of life moved from the womb to the laboratory, in the petri

dish.

As a result, we find ourselves in a world in which a global multi-billion-dollar per year fertility industry feeds reproductive tourism. Women old enough to be grandmothers become first-time mothers, and litter births like the Octumom’s (I prefer Octu vs. Octo, as she gave birth to octuplets, and she isn’t an octopus) are distressingly common. Pre-implantation genetic screening, which is in reality a “search and destroy” mission, has become the modern face of eugenics. Grandmothers are carrying their daughters’ babies (their own grandchildren) to term. Doctors are now creating three-parent embryos using DNA from two women and one man.  Single-by-choice

mothers and fathers, same-sex parents, and parenting partnerships

between non-romantically involved couples have become “The New Normal.”

Single-by-choice

mothers and fathers, same-sex parents, and parenting partnerships

between non-romantically involved couples have become “The New Normal.”

Single-by-choice

mothers and fathers, same-sex parents, and parenting partnerships

between non-romantically involved couples have become “The New Normal.”

Single-by-choice

mothers and fathers, same-sex parents, and parenting partnerships

between non-romantically involved couples have become “The New Normal.”

Stanford law professor Hank Greely, in a talk titled “The End of Sex,”

made the bold assertion that within the next fifty years the majority

of babies in developed countries will be made in the lab because no one

will want to leave their children’s lives to nature’s chance.

Indeed, we see a shift away from helping infertile couples have a child to helping adults produce the types of children they desire. The child is no longer a good end in and of itself, but a consumer product to be designed—made not begotten—and

discarded if imperfect. This is a shift away from a medical model of

trying to treat, heal, and restore natural fertility, and toward the

manufacturing of babies. In the United States alone, we are fast

approaching the million mark of frozen babies in the

laboratory—so-called “surplus” embryos.

But the veneer is coming off, and the realities of these modern solutions to help people have a baby are being exposed.

First, there are the hard data, which

continue to show how many fertility treatments fail. The most recent

data we have are from 2010; the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention  annual reports

show that 100,824 IVF cycles were performed in the United States using

non-donor eggs. Only 19 percent of those cycles resulted in a live

birth, meaning that over 80,000 of the IVF cycles failed. These figures

have not changed significantly over the last five years.

annual reports

show that 100,824 IVF cycles were performed in the United States using

non-donor eggs. Only 19 percent of those cycles resulted in a live

birth, meaning that over 80,000 of the IVF cycles failed. These figures

have not changed significantly over the last five years.

annual reports

show that 100,824 IVF cycles were performed in the United States using

non-donor eggs. Only 19 percent of those cycles resulted in a live

birth, meaning that over 80,000 of the IVF cycles failed. These figures

have not changed significantly over the last five years.

annual reports

show that 100,824 IVF cycles were performed in the United States using

non-donor eggs. Only 19 percent of those cycles resulted in a live

birth, meaning that over 80,000 of the IVF cycles failed. These figures

have not changed significantly over the last five years.

This high failure rate shifts the problem

to healthy young women who are courted with large sums of money to

“donate” their eggs to help make babies. The first recorded birth using

donor eggs was in 1983, just five years after the birth of Louise Brown. What follows is scandalous.

No central registry

tracking egg donors and their health over their lifetime exists, even

though there is precedent for such a registry in how we track living

organ donors and organ recipients. No long-term safety studies have been

done to show how many egg donors go on to have complications with their

own fertility or to develop cancers

that are known risks for women taking the drugs involved. There is no

tracking of the children created from donor eggs. And there seem to be

no ethical qualms about paying women thousands of dollars to “donate”

their eggs, even though we know how coercive money can be, and how it

works against making truly informed choices.

The harms and dangers of egg donation are slowly emerging. Much of my work

over the past several years has been gathering and telling the stories

of women harmed. Young women, struggling financially, see an ad asking

them to “be an angel,” “make a difference,” or to “ help make dreams come true.”

As one egg donor asked, “Who doesn’t want to see themselves like this?”

Sadly, she went on to suffer a torsioned ovary a few days after her

eggs were harvested. Losing an ovary compromised her fertility. A few

years later, she developed breast cancer in both breasts, as a young

woman with no previous medical history of cancer. All for a few thousand

dollars to help another.

help make dreams come true.”

As one egg donor asked, “Who doesn’t want to see themselves like this?”

Sadly, she went on to suffer a torsioned ovary a few days after her

eggs were harvested. Losing an ovary compromised her fertility. A few

years later, she developed breast cancer in both breasts, as a young

woman with no previous medical history of cancer. All for a few thousand

dollars to help another.

help make dreams come true.”

As one egg donor asked, “Who doesn’t want to see themselves like this?”

Sadly, she went on to suffer a torsioned ovary a few days after her

eggs were harvested. Losing an ovary compromised her fertility. A few

years later, she developed breast cancer in both breasts, as a young

woman with no previous medical history of cancer. All for a few thousand

dollars to help another.

help make dreams come true.”

As one egg donor asked, “Who doesn’t want to see themselves like this?”

Sadly, she went on to suffer a torsioned ovary a few days after her

eggs were harvested. Losing an ovary compromised her fertility. A few

years later, she developed breast cancer in both breasts, as a young

woman with no previous medical history of cancer. All for a few thousand

dollars to help another. My

work with egg donors has brought me face to face with the recklessness

of the fertility industry, its work to suppress the risks and dangers of

egg donation, and its refusal to do any research that might not support

its claims that egg donation is safe. The truth is, egg donation is

risky, and in some rare cases can even lead to death.

My

work with egg donors has brought me face to face with the recklessness

of the fertility industry, its work to suppress the risks and dangers of

egg donation, and its refusal to do any research that might not support

its claims that egg donation is safe. The truth is, egg donation is

risky, and in some rare cases can even lead to death.

A few studies have come out touting the

successes of egg donation. But when you get past the headlines, what you

find is that these successes refer to pregnancy outcomes, not to the

health of the woman who “donates” her eggs. A recent issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association devotes space to a new study on egg donation, but it is in the editorial

where the truth is found: “data regarding outcomes on oocyte donation

cycles have an important limitation—no data on health outcome in

donors.”

The practice of surrogacy is becoming

more prevalent and more widely accepted as a solution to helping people

have a child. In 2007, Time magazine listed “The 10 Best Chores to Outsource.” While you would expect to find lawn mowing or housecleaning on such a list, the number one chore to outsource—number one—was

pregnancy. Factors driving the rise in the use of surrogacy include the

high failure rate of many of the assisted reproductive technologies and

the rise of same-sex parenting, which, in the case of two male parents,

requires both donor eggs and a surrogate womb. Surrogacy—either

“traditional” or “gestational”—intentionally sets up a negative

environment. Instead of encouraging women to bond with their child in utero, for the benefit of both mother and child, surrogacy demands that the mother not bond with her child.

Like egg donation, surrogacy is harmful

to both the woman who carries the child and to the child. The health

risks to the woman, who must take powerful synthetic hormones to prepare

her body to accept an embryo, are real and serious. Most surrogacy contracts

require that the surrogate mother already have children as proof that

she is able to carry a child to term. However, no one has done any

studies on these existing children who observe their mothers keeping

some babies and giving others away.  The

message surrogacy sends to these children seems both clear and

dangerous: mommy keeps some of her babies, and mommy gives some of her

babies away to nice people who can’t have babies of their own. And often

mommy is paid to do this.

The

message surrogacy sends to these children seems both clear and

dangerous: mommy keeps some of her babies, and mommy gives some of her

babies away to nice people who can’t have babies of their own. And often

mommy is paid to do this.

The

message surrogacy sends to these children seems both clear and

dangerous: mommy keeps some of her babies, and mommy gives some of her

babies away to nice people who can’t have babies of their own. And often

mommy is paid to do this.

The

message surrogacy sends to these children seems both clear and

dangerous: mommy keeps some of her babies, and mommy gives some of her

babies away to nice people who can’t have babies of their own. And often

mommy is paid to do this.

Women who decide to become surrogates are

often motivated by the financial gains they are offered. Even the

promise of “just” living expenses can be an enticement for a woman of

low income with children in the home. Make no mistake: it will not be

wealthy women who line up to make themselves available to gestate

babies. It will, however, be wealthy individuals or couples who seek to

buy such services. Surrogacy takes something as natural as a pregnant

woman nurturing her unborn child and turns it into a contractual,

commercialized endeavor. And it opens the door for all sorts of

exploitation.

What about the children? Are the kids really all right, as Hollywood

tells us? The verdict is not yet in. This is an unfolding social

experiment. But, again, the veneer has begun to crack. More and more

studies are coming out on the risks to children created via assisted

reproductive technologies. These risks include higher rates of cancer and of genetic and heart problems. More stories (and more research) are surfacing that mothers and fathers are indeed good for children. Family and kinship are real—biology matters, and genetics are important.

I often tell egg donors: you didn’t help a woman have a baby; you helped a woman have your

baby. Even Sir Elton John, who with his partner David Furnish used a

woman who sold her eggs and another who rented her womb, has lamented

that he is worried about his children growing up without a mother.

While modern reproductive technologies

began as what seemed to be good ways to help people who struggle with

infertility, from where I sit, we’ve made a real mess. The biggest

losers are the poor and vulnerable women who are exploited, as they say

in India, for “selling their motherhood.” And, of course, the children

are losers too.

One story sticks in my head. A surrogate

mother for a gay couple, right after she gave birth, realized she

couldn’t surrender the child—so she went to court to get shared custody.

The daughter, being raised by the gay couple and the surrogate mother,

one day asked her surrogate mother a very poignant question: since she

looked like her biological mother, why is it that her mommy gave

her away? The little girl simply could not understand how her mother

would do this. The surrogate mother’s response? “I didn’t know what to

tell her.”

I wouldn’t know what to tell that little girl either. Maybe we should just stop making such messes.