A friend of mine, a political scientist, recently posed two very good questions. They go right to the heart of our discussion today. He wondered, first, if the religious freedom debate had “crossed a Rubicon” in our country’s political life. And second, he asked if Catholic bishops now found themselves opposed—in a new and fundamental way—to the spirit of American society.

We should begin by recalling that even at the height of anti-Catholic bigotry, Catholics have always served our country with distinction. More than eighty Catholic chaplains died in World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. All four chaplains who won the Medal of Honor in those wars were Catholic priests.

Time and again, Catholics have proven their love of our nation with their talent, hard work, and blood. So if the bishops of the United States ever find themselves opposed, in a fundamental way, to the spirit of our country, the fault won’t lie with our bishops. It will lie with political and cultural leaders who turned our country into something it was never meant to be.

That said, let’s turn to my friend’s first question. The Rubicon is a river in northern Italy. It’s small and forgettable, except for one thing. During the Roman Republic, it marked a border. To the south lay Italy, ruled directly by the Roman Senate. To the north lay Gaul, ruled by a governor. Under Roman law, no general could enter Italy with an army. Doing so carried the death penalty. In 49 BC, when Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon with his Thirteenth Legion and marched on Rome, he triggered a civil war and changed the course of history. Ever since then, “crossing the Rubicon” has meant passing a point of no return.

Caesar’s march on Rome is a very long way from our nation’s current disputes over religious liberty. But “crossing the Rubicon” is still a useful image. My friend’s point is this: Have we, in fact, crossed a border in our country’s history—the line between a religion-friendly past, and an emerging America much less welcoming to Christian faith and witness?

Let me describe the nation we were, and the nation we’re becoming. Then you can judge for yourselves.

People often argue about whether America’s Founders were mainly Christian, mainly Deist, or both of the above. It’s a reasonable debate. It won’t end any time soon. But no one can reasonably dispute that the Founders’ moral framework was overwhelmingly shaped by Christian faith. And that makes sense because America was largely built by Christians. The world of the American Founders was heavily Christian, and they saw the value of publicly engaged religious faith because they experienced its influence themselves. They created a nation designed in advance to depend on the moral convictions of religious believers, and to welcome their active role in public life.

The Founders also knew that religion is not just a matter of private conviction. It can’t be reduced to personal prayer or Sunday worship. It has social implications. The Founders welcomed those implications. Christian faith demands preaching, teaching, public witness, and service to others—by each of us alone, and by acting in cooperation with fellow believers. As a result, religious freedom is never just freedom from repression but also—and more importantly—freedom for active discipleship. It includes the right of religious believers, leaders, and communities to engage society and to work actively in the public square. For the first 160 years of the republic, cooperation between government and religious entities was the norm in addressing America’s social problems. And that brings us to our country’s current situation.

Americans have always been a religious people. They still are. Roughly 80 percent of Americans call themselves Christians. Millions of Americans take their faith seriously. Millions act on it accordingly. Religious practice remains high. That’s the good news. But there’s also bad news. In our courts, in our lawmaking, in our popular entertainment, and even in the way many of us live our daily lives, America is steadily growing more secular. Mainline churches are losing ground. Many of our young people spurn Christianity. Many of our young adults lack any coherent moral formation. Even many Christians who do practice their religion follow a kind of easy, self-designed gospel that led author Ross Douthat to call us a “nation of heretics.”1 Taken together, these facts suggest an American future very different from anything in our nation’s past.

There’s more. Contempt for religious faith has been growing in America’s leadership classes for many decades, as scholars such as Christian Smith and Christopher Lasch have shown.2 But in recent years, government pressure on religious entities has become a pattern, and it goes well beyond the current administration’s Health and Human Services mandate. It involves interfering with the conscience rights of medical providers, private employers, and individual citizens. And it includes attacks on the policies, hiring practices, and tax statuses of religious charities, hospitals, and other ministries. These attacks are real. They’re happening now. And they’ll get worse as America’s religious character weakens.

This trend is more than sad. It’s dangerous. Our political system presumes a civil society that pre-exists and stands outside the full control of the state. In the American model, the state is meant to be modest in scope and constrained by checks and balances. Mediating institutions such as the family, churches, and fraternal organizations feed the life of the civic community. They stand between the individual and the state. And when they decline, the state fills the vacuum they leave. Protecting these mediating institutions is therefore vital to our political freedom. The state rarely fears individuals, because alone, individuals have little power. They can be isolated or ignored. But organized communities are a different matter. They can resist. And they can’t be ignored.

This is why, for example, if you want to rewrite the American story into a different kind of social experiment, the Catholic Church is such an annoying problem. She’s a very big community. She has strong beliefs. And she has an authority structure that’s very hard to break—the kind that seems to survive every prejudice and persecution, and even the worst sins of her own leaders. Critics of the Church have attacked America’s bishops so bitterly, for so long, over so many different issues—including the abuse scandal, but by no means limited to it—for very practical reasons. If a wedge can be driven between the pastors of the Church and her people, then a strong Catholic witness on controversial issues breaks down into much weaker groups of discordant voices.

Having said all this, the title of my comments is “building a culture of religious freedom.” So how do we do that?

We can start by changing the way we habitually think. Democracy is not an end in itself. Majority opinion does not determine what is good and true. Like every other form of social organization and power, democracy can become a form of repression and idolatry. The problems we now face in our country didn’t happen overnight. They’ve been growing for decades, and they have moral roots. America’s bishops named the exile of God from public consciousness as “the root of the world’s travail today” nearly sixty-five years ago. And they accurately predicted the effects of a life without God on the individual, the family, education, economic activity, and the international community.3 Obviously, too few people listened.

We also need to change the way we act. We need to understand that we can’t quick-fix our way out of problems we behaved ourselves into. Catholics have done very well in the United States. As I said earlier, most of us have a deep love for our country, its freedoms, and its best ideals. But this is not our final home. There is no automatic harmony between Christian faith and American democracy. The eagerness of Catholics to push their way into our country’s mainstream over the past half century, to climb the ladder of social and economic success, has done very little to Christianize American culture. But it’s done a great deal to weaken the power of our Catholic witness.

In the words of scholar Robert Kraynak, democracy—for all of its strengths—also “has within it the potential for its own kind of ‘social tyranny.’” The reason is simple. Democracy advances “the forces of mass culture which lower the tone of society . . . by lowering the aims of life from classical beauty, heroic virtues and otherworldly transcendence to the pursuits of work, material consumption and entertainment.” This inevitably tends to “[reduce] human life to a one-dimensional materialism and [an] animal existence that undermines human dignity and eventually leads to the ‘abolition of man.’”4

To put it another way: The right to pursue happiness does not include a right to excuse or ignore evil in ourselves or anyone else. When we divorce our politics from a grounding in virtue and truth, we transform our country from a living moral organism into a kind of golem of legal machinery without a soul.

This is why working for good laws is so important. This is why getting involved politically is so urgent. This is why every one of our votes matters. We need to elect the best public leaders, who then create the best policies and appoint the best judges. This has a huge impact on the kind of nation we become. Democracies depend for their survival on people of conviction fighting for what they believe in the public square—legally and peacefully, but zealously and without apologies. That includes you and me.

Critics often accuse faithful Christians of pursuing a “culture war” on issues such as abortion, sexuality, marriage and the family, and religious liberty. And in a sense, they’re right. We are fighting for what we believe. But of course, so are advocates on the other side of all these issues—and neither they nor we should feel uneasy about it. Democracy thrives on the struggle of competing ideas. We steal from ourselves and from everyone else if we try to avoid that struggle. In fact, two of the worst qualities in any human being are cowardice and acedia—and by acedia I mean the kind of moral sloth that masquerades as “tolerance” and leaves a human soul so empty of courage and character that even the devil Screwtape would spit it out.5

In real life, democracy is built on two practical pillars: cooperation and conflict. It requires both. Cooperation, because people have a natural hunger for solidarity that makes all community possible. And conflict, because people have competing visions of what is right and true. The more deeply they hold their convictions, the more naturally people seek to have those convictions shape society.

What that means for Catholics is this: We have a duty to treat all persons with charity and justice. We have a duty to seek common ground where possible. But that’s never an excuse for compromising with grave evil. It’s never an excuse for being naive. And it’s never an excuse for standing idly by while our liberty to preach and serve God in the public square is whittled away. We need to work vigorously in law and politics to form our culture in a Christian understanding of human dignity and the purpose of human freedom. Otherwise, we should stop trying to fool ourselves that we really believe what we claim to believe.

There’s more. To work as it was intended, America needs a special kind of citizenry; a mature, well-informed electorate of persons able to reason clearly and rule themselves prudently. If that’s true—and it is—then the greatest danger to American liberty in our day is not religious extremism. It’s something very different. It’s a culture of narcissism that cocoons us in dumbed-down, bigoted news, vulgarity, distraction, and noise, while methodically excluding God from the human imagination. Kierkegaard once wrote that “the introspection of silence is the condition of all educated intercourse,” and that “talkativeness is afraid of the silence which reveals its emptiness.”6 Silence feeds the soul. Silence invites God to speak. And silence is exactly what American culture no longer allows. Securing the place of religious freedom in our society is therefore not just a matter of law and politics, but of prayer, interior renewal—and also education.

We need to re-examine the spirit that has ruled the Catholic approach to American life for the past sixty years. In forming our priests, deacons, teachers, and catechists—and especially the young people in our schools and religious education programs—we need to be much more penetrating and critical in our attitudes toward the culture around us. We need to recover our distinctive Catholic identity and history. Then we need to act on them. America is becoming a very different country, and as Ross Douthat argues so well in his excellent book Bad Religion, a renewed American Christianity needs to be ecumenical, but also confessional. Why? Because “in an age of institutional weakness and doctrinal drift, American Christianity has much more to gain from a robust Catholicism and a robust Calvinism, than it does from even the most fruitful Catholic-Calvinist theological dialogue.”7

America is now mission territory. Our own failures helped to make it that way. We need to admit that. Then we need to re-engage the work of discipleship to change it.

I want to close by returning to the second of my friend’s two questions. He asked if our nation’s Catholic bishops now find themselves opposed—in a new and fundamental way—to the spirit of American society. I can speak only for myself. But I suspect that for many of my brother American bishops, the answer to that question is a mix of both no and yes.

The answer is “no” in the sense that the Catholic Church has always thrived in the United States, even in the face of violent bigotry. Catholics love and thank God for this country. They revere the American legacy of democracy, law, and ordered liberty. As the bishops wrote in 1940 on the eve of World War II, “[we] renew [our] most sacred and sincere loyalty to our government and to the basic ideals of the American Republic . . . [and we] are again resolved to give [ourselves] unstintingly to its defense and its lasting endurance and welfare.”8 Hundreds of thousands of American Catholics did exactly that on the battlefields of Europe and the South Pacific.

But the answer is “yes” in the sense that the America of Catholic memory is not the America of the present moment or the emerging future. Sooner or later, a nation based on a degraded notion of liberty, on license rather than real freedom—in other words, a nation of abortion, disordered sexuality, consumer greed, and indifference to immigrants and the poor—will not be worthy of its founding ideals. And on that day, it will have no claim on virtuous hearts.

In many ways I believe my own generation, the boomer generation, has been one of the most problematic in our nation’s history because of our spirit of entitlement and moral superiority; our appetite for material comfort unmoored from humility; our refusal to acknowledge personal sin and accept our obligations to the past.

But we can change that. Nothing about life is predetermined except the victory of Jesus Christ. We create the future. We do it not just by our actions, but by what we really believe—because what we believe shapes the kind of people we are. In a way, “growing a culture of religious freedom” is the better title for these comments. A culture is more than what we make or do or build. A culture grows organically out of the spirit of a people—how we live, what we cherish, what we’re willing to die for.

If we want a culture of religious freedom, we need to begin it here, today, now. We live it by giving ourselves wholeheartedly to God and the Gospel of Jesus Christ—by loving God with passion and joy, confidence and courage; and by holding nothing back. God will take care of the rest. Scripture says, “Unless the Lord builds the house, those who build it labor in vain” (Ps 127:1). In the end, God is the builder. We’re the living stones. The firmer our faith, the deeper our love, the purer our zeal for God’s will—then the stronger the house of freedom will be that rises in our own lives, and in the life of our nation.

Charles J. Chaput, O.F.M. Cap., Roman Catholic Archbishop of Philadelphia, is the author of Render Unto Caesar: Serving the Nation by Living Our Catholic Beliefs in Political Life.This essay is adapted from a lecture Archbishop Chaput delivered yesterday at the Napa Institute’s 2012 annual conference.

Receive Public Discourse by email, become a fan of Public Discourse on Facebook, follow Public Discourse on Twitter, and sign up for the Public Discourse RSS feed.

Support the work of Public Discourse by making a secure donation to The Witherspoon Institute.

Copyright 2012 the Witherspoon Institute. All rights reserved.

[1] For patterns of religious belief in various age groups, see Barna Group and Pew Research Center data. For the state of moral formation among young adults, see Christian Smith, editor, Lost in Transition: The Dark Side of Emerging Adulthood, Oxford University Press, New York, 2011. For an overview of American religious trends and their meaning, see Ross Douthat, Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics, Free Press, New York, 2012

[2] See Christopher Lasch, The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy, W.W. Norton, New York, 1995; and Christian Smith, editor, The Secular Revolution: Power, Interests and Conflict in the Secularization of American Public Life, University of California Press, Los Angeles, 2003

[3] “Secularism,” a pastoral statement by the Administrative Board of the National Catholic Welfare Conference, on behalf of the bishops of the United States, November 14, 1947; as collected in Pastoral Letters of the American Hierarchy, 1792-1970, Hugh J. Nolan, editor, Our Sunday Visitor, Huntington, IN, 1971

[4] Robert Kraynak, “Citizenship in Two Worlds: On the Tensions between Christian Faith and American Democracy,” Josephinum Journal of Theology, Vol. 16, No. 2, 2009; see also a more extensive discussion of this theme in his book, Christian Faith and Modern Democracy: God and Politics in the Fallen World, University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, IN, 2001

[5] C.S. Lewis, see his “Screwtape Proposes a Toast” in The Screwtape Letters, HarperCollins, New York, 2001

[6] Soren Kierkegaard, The Present Age: On the Death of Rebellion, HarperPerennial, New York, 2010, p. 44-45

[7] Douthat, Bad Religion, p. 286-287

[8] “The American Republic,” a statement by the bishops of the United States, November 13, 1940; as collected in Pastoral Letters of the American Hierarchy, 1792-1970

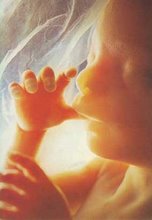

Were there to be no support in the whole history of ethical and moral thought, were there no acknowledged confirmation from medical science, were the history of legal opinion to the contrary, we would still have to conclude on the basis of God's Holy Word that the unborn child is a person in the sight of God. He is protected by the sanctity of life graciously given to each individual by the Creator, Who alone places His image upon man and grants them any right to life which they have.

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

Building a Culture of Religious Freedom by Charles J. Chaput