This

past weekend and into this week, the Internet was abuzz with chatter

about an article seriously examining the justification of infanticide.

And the proposition originated in the Journal of Medical Ethics!

Political

pundits and bloggers were Tweeting and writing about an article from

two years ago on Slate.com which debated the points made by ethicists

Alberto Giubilini and Francesca Minerva in the Journal of Medical Ethics.

It's not clear what sparked the renewed interest in the article, but

it's important to once again tackle this issue and respond to the

disturbing propositions threatening innocent life.

HLI Fellow Dr. Denise Hunnell wrote an article responding to the ethicists' claims back in 2012 when the story first broke. HLI reprinted the article this week on our Truth and Charity Forum, and I wanted to share it with you in our newsletter. God bless.

Sincerely yours in Christ,

Father Shenan J. Boquet

President, Human Life International

Father Shenan J. Boquet

President, Human Life International

After Birth Abortion: A Modest Proposal?

by Denise Hunnell, M.D.

Let

us consider two excerpts, and see if we can determine which comes from

the realm of fiction, and which comes from the field of modern ethics.

The first:

That the remaining hundred thousand may, at a year old, be offered in the sale to the persons of quality and fortune through the kingdom; always advising the mother to let them suck plentifully in the last month, so as to render them plump and fat for a good table. A child will make two dishes at an entertainment for friends; and when the family dines alone, the fore or hind quarter will make a reasonable dish, and seasoned with a little pepper or salt will be very good boiled on the fourth day, especially in winter.

And the second:

Abortion is largely accepted even for reasons that do not have anything to do with the fetus' health. By showing that (1) both fetuses and newborns do not have the same moral status as actual persons, (2) the fact that both are potential persons is morally irrelevant and (3) adoption is not always in the best interest of actual people, the authors argue that what we call 'after-birth abortion' (killing a newborn) should be permissible in all the cases where abortion is, including cases where the newborn is not disabled. (After-birth abortion: Why should the baby live? Journal of Medical Ethics, February 23, 2012)

I suppose the jargon in the latter gives it away.

When I first read the latter, an abstract from the article "After-birth abortion: Why should the baby live?" published in the Journal of Medical Ethics, I was hoping it would be the prelude of an updated version of Jonathan Swift's eighteenth century work A Modest Proposal,

from which the first excerpt is drawn,In Swift's eerily prescient

satire, the protagonist argues that the solution to poverty is to eat

the children of the poor.

Alarmingly,

unlike Jonathan Swift's work, the abstract is not from a work of

satire. It is ostensibly a serious presentation by ethicists Alberto

Giubilini and Francesca Minerva, who argue that parents should be

allowed to kill newborn infants for any reason that is currently used

to justify abortion. In fact, they do not constrain their proposal to a

specific time period after birth but claim that a child has no right to

life until she adequately demonstrates the very nebulous and

subjective characteristic of "self-awareness".

Giubilini

and Minerva are not, at least not in this article, arguing that the

killed children should also be eaten. Fortunately, that detail of

Swift's solution remains fiction. Even so, the expressions of outrage

over this piece have been harsh and swift. Indeed, the editor of the Journal of Medical Ethics felt compelled to release a statement defending the publication of this provocative article, although the defense was weak at best.

That an argument for killing newborns would be made should not be surprising. Similar reasoning was put forth by Michael Tooley in 1972 and by Peter Singer in 1993.

Giubilini and Minerva simply extend these arguments to include killing

perfectly healthy newborns that merely pose a burden or inconvenience

to their mothers or to society as a whole. In addition, they argue that

logic demands the option to kill disabled infants, especially those

with genetic diseases like Downs syndrome, when the diagnosis is not

made until after birth. Why, they ask, should a woman have every option

including abortion before birth, and no options after birth?

As

reprehensible as their conclusions are, Giubilini and Minerva agree

with pro-lifers on two key points. First, they fully accept that the

unborn and the newborn are both living human beings, accepting without

argument the scientific reality that a biological human being begins at

conception. Thus, they forthrightly acknowledge that both abortion and

infanticide involve the taking of human life.

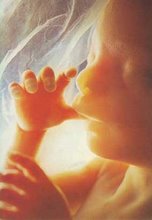

Second,

Giubilini and Minerva agree that the event of birth is irrelevant to

the moral status of both the unborn child and the newborn. In order to

make their proposal more palatable, they eschew the term "infanticide"

to emphasize that the lives of the newborn and the fetus carry the same

moral weight. In this, they find agreement with the Catholic Church

and all who recognize the full humanity of the unborn child. There is

absolutely no difference in the moral standing of a child in the womb

and a newborn in her mother's arms.

If

they have such essential points right, how do they end up so wrong?

Their errors begin when they assign the arbitrary status of "potential

person" to both the unborn and the newborn. With absolutely no

justification other than their own opinion for such an assertion, they

echo Peter Singer in declaring that while the unborn and newborn are

living human beings, they lack the self-awareness to qualify as "actual

persons." In fact, also following Singer, the authors go so far as to

claim that personhood is a characteristic that can be assigned to

non-human animals that demonstrate a sense of self:

Both

a fetus and a newborn certainly are human beings and potential

persons, but neither is a 'person' in the sense of 'subject of a moral

right to life'. We take 'person' to mean an individual who is capable of

attributing to her own existence some (at least) basic value such that

being deprived of this existence represents a loss to her. This means

that many non- human animals and mentally retarded human individuals

are persons, but that all the individuals who are not in the condition

of attributing any value to their own existence are not persons. Merely

being human is not in itself a reason for ascribing someone a right to

life.

Giubilini

and Minerva go on to declare that when "aborting" a "potential

person," no life is really lost. A true person never existed.

Therefore, one cannot destroy what never was.

What

Giubilini and Minerva cannot justify is their authority to declare

some human beings as "potential persons." If they can dismiss the life

and dignity of a newborn child based on the lack of an arbitrary

concept of self-awareness, what is to stop others from declaring that

true personhood requires a specific level of intelligence or gender or

race or creed?

What

Giubilini and Minerva effectively do is subjugate the life and dignity

of the vulnerable to the whims of the powerful, who are allowed to

determine who is and who is not a person. This is the fatal flaw of

attributing human dignity based on some external evaluation. Either one

accepts that every human being is worthy of life and dignity, or you

are forced to adopt capricious and subjective metrics as the basis of

one's claim to rights and dignity. It takes great arrogance to presume

both the wisdom to judge which human lives are worth living as well as

the prescience to know whose life will be too burdensome.

The

fundamental error of Giubilini and Minerva is that they fail to

recognize that every human being is of inestimable worth. The dignity

of every human life is an intrinsic characteristic - it cannot be

granted or denied according to some arbitrary algorithm. Further, the

term "potential person" has no basis in science, although this error is

not unique to Giubilini and Minerva: It is common to all those who

advocate for abortion, euthanasia, embryonic stem cell research, or any

other actions that relegate human lives to a disposable status.

Perhaps

now those who have thus far seen room for a "compromise" in the areas

of abortion and other beginning-of-life issues might recognize the

urgency of reaffirming the dignity and value of every human being

without exception. No one who allows that some human beings are more

valuable than others can honestly be shocked and outraged by Giubilini

and Minerva's argument. These ethicists merely carry this sadly common

premise to its logical conclusion, and offer a very "Modest Proposal".